How does a magnet work?

When you bring a magnet close to a spoon, it attracts it – even though it doesn’t even touch it. This ability to act at a distance is a consequence of the magnetic field that a magnet creates around itself. It is precisely thanks to it that a magnet attracts or repels other magnets and acts on ferromagnetic materials (e.g. iron or ordinary steel).

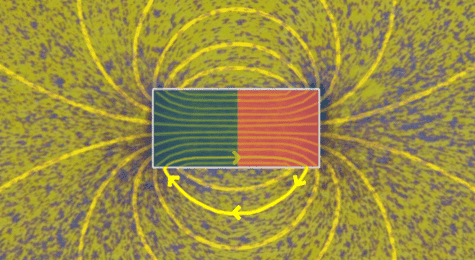

The magnetic field is invisible, but it can be illustrated using iron filings. If we place a magnet under a sheet of paper and sprinkle filings on it, they will spontaneously arrange themselves into characteristic lines. These correspond to the so-called magnetic field lines, which show its direction and relative intensity. The denser the field lines are, the stronger the magnetic field is at that place [00:23].

Notice that magnetic field lines emerge from one end of the magnet and enter the opposite end, which gives them a defined direction. At the same time, they form closed loops – they always close in on themselves and create a continuous circuit. The place where the magnetic field lines emerge from the magnet, and the place where they enter it, are called the poles of the magnet:

- from the north pole (N) the field lines emerge,

- into the south pole (S) the field lines enter.

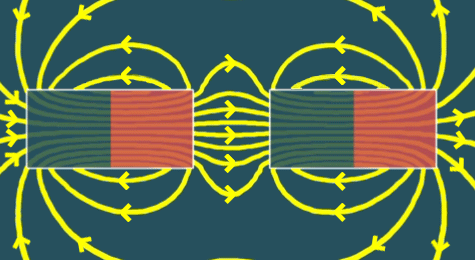

It is precisely this direction and closure of magnetic field lines, together with the field’s tendency to arrange itself as smoothly and as energetically advantageously as possible, that explains the behaviour of two magnets in close proximity.

Although each magnet could close its field lines “into itself”, if the opposite pole of another magnet is nearby, the field will prefer a smoother and energetically more advantageous path for the field lines. Therefore, with opposite poles (N–S), the field lines connect between the magnets and create one common magnetic field. The result is attraction.

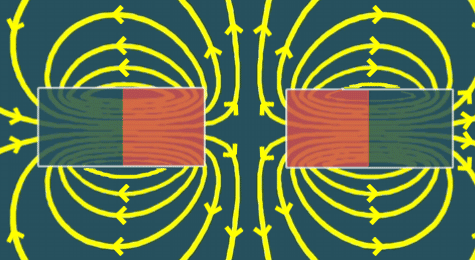

Conversely, when the same poles (N–N or S–S) are facing each other, the field lines cannot connect smoothly – they would be directed against each other. Such an arrangement is energetically disadvantageous, and therefore the magnetic field is pushed out into the surroundings. This “expansion” of the field outward appears externally as repulsion of the magnets.

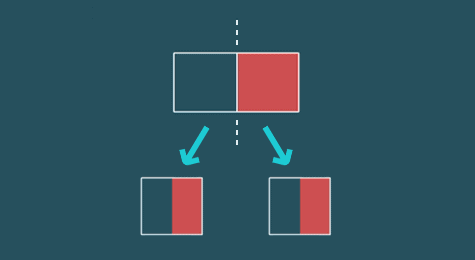

You might think of the question: is it possible to obtain only a north pole or only a south pole from a magnet? No. A “pole” is not a part of the magnet that you could take away – it is only the place where the magnetic field lines emerge from the magnet, and the place where they enter it. Since the magnet’s magnetic field forms closed loops, there must always be both an exit and an entry.

Therefore, when you cut a magnet, you do not cut off the north pole from the south pole. The magnetic field in each part rearranges again so as to form closed loops – and in this way two new pairs of exit and entry locations are created. The result is two smaller magnets, each again with its own north and south pole. And this principle also applies when dividing into ever smaller parts; a separate “single pole” will not appear.

– always with their own north and south pole.

We already know that there are always two poles. But where does the magnetic field as such come from? We have to look for the answer at the level of atoms – in electrons, their spin, and in how their magnetic effects in atoms (and between atoms) add up or cancel each other out. This is precisely what determines whether a material is attractable by a magnet, whether it can arrange itself so that it becomes a magnet with its own magnetic field – or whether its reaction to a magnetic field is so weak that in everyday life we practically do not notice it.

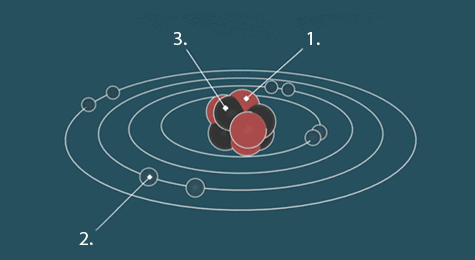

To understand where the magnetic field comes from, we must look at the level of atoms. At the centre of the atom is the nucleus, made up of positively charged protons and electrically neutral neutrons. Surrounding the nucleus are negatively charged electrons.

We know that electrons, protons and neutrons have mass. Protons and electrons have electric charge. Do these particles have any other property?

Yes, there is one that is absolutely essential for magnetism, even though it is not often discussed. It is called spin.

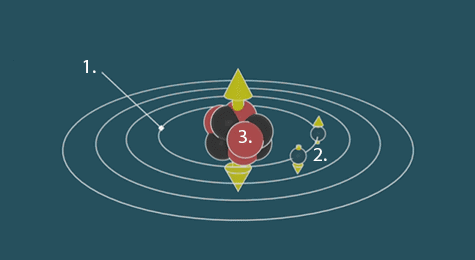

Spin is a purely quantum property that has no counterpart in classical physics. As a consequence of it, elementary particles have a magnetic moment, that is, a magnetic effect. In simple terms, we can therefore imagine them as tiny magnets.

All elementary particles have spin, but in electrons its magnetic influence is the most significant. That is why electrons are key from the perspective of magnetism.

The spin of the electron is therefore the main contribution to the magnetism of the atom, though not the only one. When an electron moves around the nucleus, it behaves like a tiny electric current – and every current creates a magnetic field. This field is the second contribution to the magnetism of the atom and is called the orbital magnetic field.

It may therefore seem that every atom must be magnetic – electrons have a magnetic moment given by spin and at the same time move within the atom, thereby creating an orbital magnetic field as well. At first glance, every atom should therefore be magnetic, and consequently every material composed of such atoms.

In reality, however, it is not that simple. In many atoms, the magnetic effects of electrons cancel each other out, so the atom as a whole has no resulting magnetic moment. And even in cases where individual atoms do have a magnetic moment, this still does not mean that the material will be magnetic externally – either as a magnet, or by responding noticeably to a magnetic field.

For a material to be magnetic as a whole, it is not enough that electrons have spin and create a magnetic field. Several conditions must be met at multiple levels:

- Favourable arrangement of electrons in the atom – so that the atom has a magnetic moment, typically due to the presence of unpaired electrons.

- Favourable mutual arrangement of atoms in a solid – so that the magnetic moments of neighbouring atoms can align with each other and enable the formation of magnetic domains.

- Favourable arrangement and behaviour of magnetic domains – so that the material behaves externally as a magnet.

Let us look at the individual conditions in more detail:

1. Favourable arrangement of electrons in the atomElectrons in an atom occupy so-called orbitals, and one orbital can contain at most two electrons. If there are two electrons in an orbital, they have opposite spins, and their magnetic effects therefore largely cancel each other out. Similarly, contributions related to their motion within the atom can also cancel out.

A fully occupied orbital therefore usually does not contribute to the overall magnetism of the atom. For an atom to contribute to magnetism, it must have at least one unpaired electron – that is, an electron that is alone in an orbital.

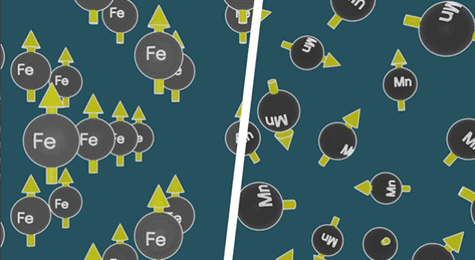

2. Favourable mutual arrangement of atoms in a solidThe mere presence of unpaired electrons and the magnetic effect of individual atoms is still not enough for the material as a whole to behave like a magnet.

This is because the magnetism of the material as a whole is also influenced by the arrangement of atoms in a solid. In some materials, the magnetic moments of neighbouring atoms can align in the same direction, which is energetically favourable for the system. In other materials, these moments do not arrange themselves uniformly, and the result is that the material as a whole is not magnetic.

Right: misaligned moments – their resulting magnetic effect does not manifest externally.

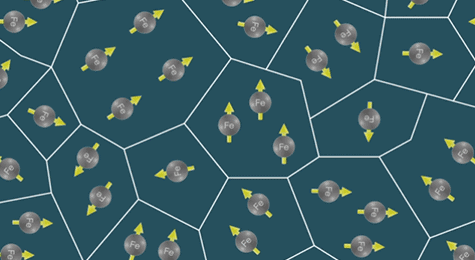

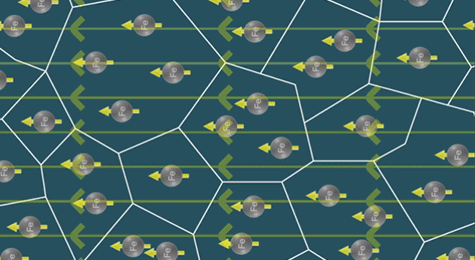

Even if the magnetic moments of atoms in a material are able to align, they do not usually align uniformly throughout the entire volume of the material. Instead, they align only locally – in smaller regions called magnetic domains.

Each piece of material usually consists of many such domains. Within one domain, the magnetic moments of atoms are oriented in the same direction, but individual domains may be oriented differently. Their magnetic effects can therefore cancel each other out.

– their magnetic effects cancel each other out.

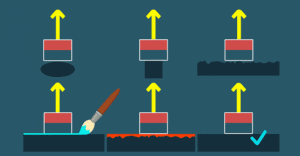

For example, in an ordinary piece of iron there are many domains that are oriented differently. Their effects therefore cancel each other out, and the iron appears externally non-magnetic. Only when the iron is placed in an external magnetic field (for example near a magnet or in a field created by an electric current) can the domains rearrange and begin to orient more uniformly. Only then does the material become a magnet.

In the previous section, we saw that the magnetism of a material is determined by the behaviour of magnetic domains. Now an important question arises: what happens when the external magnetic field disappears?

The difference between materials lies in how firmly the domains are “bound” within the internal (crystal) structure of the material and how easily they can return to their original arrangement after the field is removed.

Materials in which the domains easily return to their original disordered state after the field is removed are called magnetically soft. In contrast, materials in which the domains are more firmly “anchored”, so that once they become aligned, they are able to maintain this arrangement even without an external field, are referred to as magnetically hard.

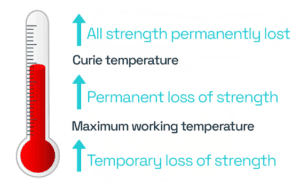

A permanent magnet is a magnetically hard material that has been magnetised – its domains have become aligned and, after the external field is removed, they do not spontaneously return to a disordered state. Therefore, it is able to maintain its own magnetic field for a long time.

Special materials and alloys are used to manufacture strong permanent magnets, for example those based on neodymium, iron and boron.

Watch the video for an even better understanding – clear visualisations and specific examples that will quickly clarify magnetism for you.